Servo Magazine ( October 2009 )

Rockin’ Robot Style

By Joe Shearer View In Digital Edition

Photos provided by Mike Rippy and David Ferguson

What are the odds a band that spent years toiling at kids’ birthday parties in a pizza joint would get a second shot at immortality? Well, if your name is the Rock-afire Explosion and your members include guitar- and banjo-playing bears, a cheerleading mouse, a keyboard-playing gorilla, and a ventriloquist wolf, you have a leg up on the competition when it comes to robot fanatics.

The Rock-afire Explosion is a gang of animatronic rockers who thrilled kids throughout the 1980s at Showbiz Pizza Place — the pizza joint-cum-video arcade-cum robot rock ‘n roll playland.

The band is a childhood legend for many Gen Xers: Fats Geronimo, the ivory-tickling gorilla; lead guitarist Beach Bear; country bear Billy Bob Brockali (with sidekick Looney Bird in a nearby oil drum) on banjo; outer-space canine Dook LaRue on drums; cheerleader mouse Mitzi Mozzarela providing vocals and moral support; and stand-up comedian Rolfe DeWolfe, a wolf who always had his trusty puppet Earl Schmerle within arm’s reach.

When Showbiz went the way of the dodo in the late 1980s, it was replaced by the more cost-efficient Chuck E. Cheese brand. It marked a passage for a generation, a reminder that the world — for better or worse — changes.

However, for a small but loyal group of fans — including David Ferguson — the birthday party never ends. Ferguson is one of a handful of collectors across the country who have taken the ultimate step in keeping their beloved characters alive: They own their own complete, fully-functional robotic rock band, complete with stage lights, props, and the various accoutrements to display and use in their man caves, guest rooms, basements, or garages.

Ferguson was determined to get the band back together, and converted the garage of his otherwise unassuming suburban Fishers, IN home into a makeshift stage. The space has been carpeted and outfitted with blacklights, transforming it into a showroom of sorts with toys, photos, posters, and other memorabilia and collectibles from the restaurants adorning the opposite wall.

So, why go to the trouble and expense of installing them in your own home when there is a large supply of reasonable facsimilies in existing Chuck E. Cheese restaurants?

For many children growing up in the 80s, Showbiz Pizza Place is something of a Valhalla, a magical place that holds special memories. Many — Ferguson among them — were left cold by the shift from Showbiz to Chuck E. Cheese, and feel like (as many do) the original incarnation is superior to what they feel is the scaled-down version that exists today.

History

Showbiz Pizza Place took a twisted, complex turn from its original incarnation in the 80s to its current identity. In 1979, a company called Topeka Inn Management struck a deal with the Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatre, which created the robotics for a live animatronic stage show with the idea of opening a chain of high-concept entertainment-themed restaurants featuring pizza, video games, and animatronic amusement.

But prior to opening the first Pizza Time franchise, Topeka Inn head Bob Brock discovered a similar, but more advanced team of robots produced by Creative Engineering, Inc. (CEI), known as “The Wolf Pack Five.”

The Wolf Pack contained full-bodied, life-sized characters, used three stages, and featured complex lighting and choreography. The Pizza Time Players — by contrast — were half-bodied, performing from a “balcony” stage that obscured the robots from the waist down, and featured about half the movement of the Wolf Pack bots with more simplistic, less realistic costumes, plus featured similar characters with little variation in movement.

“The [Wolf Pack] animatronics were quite sophisticated, arguably on par with what could be found at a Disney theme park,” said Travis Schafer, Showbiz Pizza historian and owner of www.showbizpizza.com. “The Pizza Time characters looked more like giant stuffed animals.”

Brock couldn’t pass up the more functional, better looking Wolfpack bots (and feared a competitor might snatch them up and trump his setup down the road), so he broke ties with Pizza Time and joined forces with CEI to form Showbiz Pizza Place. The Wolfpack five underwent cosmetic redesigns and became “The Rock-afire Explosion.”

Chuck E. Cheese and Showbiz grew into competing companies, and each expanded quickly during the early 1980s before falling on hard economic times. Showbiz bought out Pizza Time in June 1985, and retained rights to the Chuck E. Cheese branding, along with their own characters, running restaurants using both sets of animatronics.

Over the next several years, growing internal strife between Showbiz and CEI, along with the leverage afforded them by the rights of the Chuck E. Cheese characters, led to Showbiz dropping CEI as their animatronics provider. The Showbiz Pizza name, properties and the stores were all converted to Chuck E. Cheese operations around 1990. Chuck E. Cheese spokesperson Brenda Holloway said the decision wasn’t a hard one to make based on the potential savings.

“We found that it would be more cost-effective to just use the characters we had,” Holloway commented.

The Rock-afire Explosion shows were retrofitted to become Chuck E. Cheese characters swapping clothing and outer cosmetics, but retained much of the underlying mechanics. New stores were outfitted with newer, simpler units, often featuring just one robot with other interactive activities in place of the costlier robots. By 1990 — like any number of great bands — The Rock-afire Explosion went their separate ways.

The remaining unused Rock-afire units sat in the Orlando, FL warehouse owned by CEI founder Aaron Fechter. When Fechter decided to start selling them on eBay, Ferguson — a robotics junkie eager to dig into the guts of the show — jumped at the chance.

Inner Workings

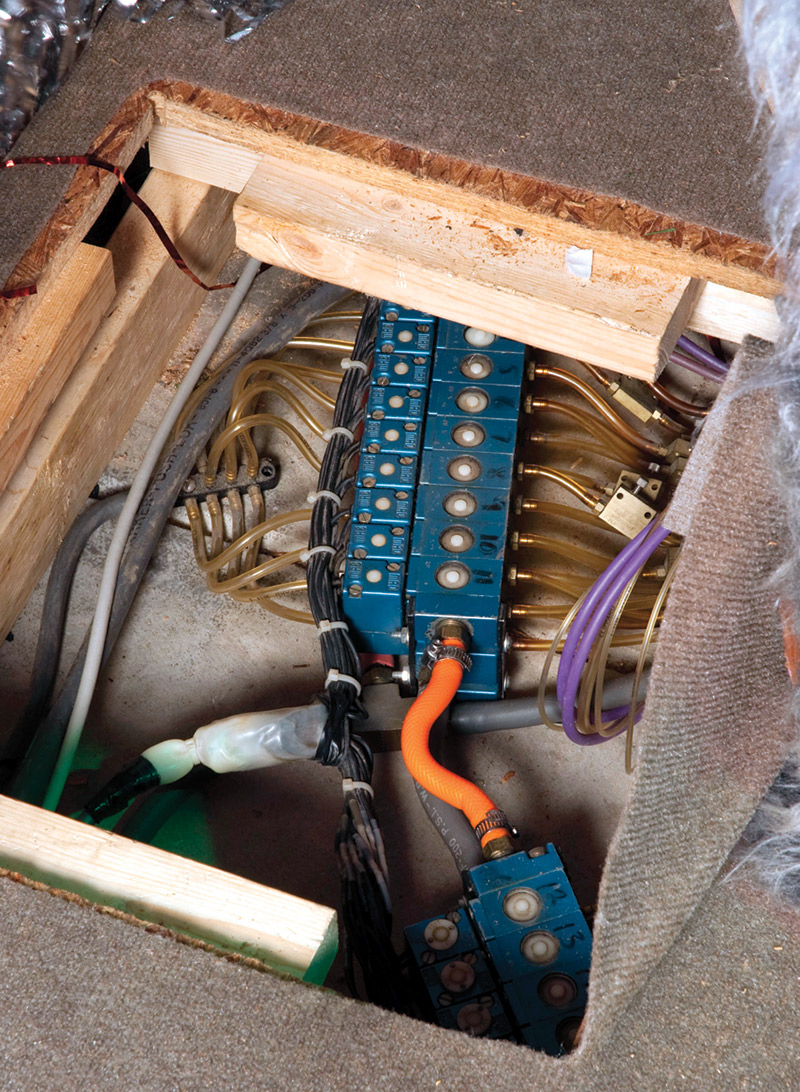

The robots function using compressed air which is forced through a series of valves and manifolds into each robot, where electrically-controlled air (MAC) valves force air through double-acting air cylinders. The air pressure translates into linear movements within each unit. Flow control valves regulate the amount of air pumping through the robots. Each valve has two ports that run to a single movement. When the valve is turned on, port A pushes air into the cylinder, while port B exhausts air from the cylinder. Turning off the valve alternates each port’s function.

The robots movements are controlled by switching air valves on and off. Each robot is controlled by roughly 18 of these 24V valves.

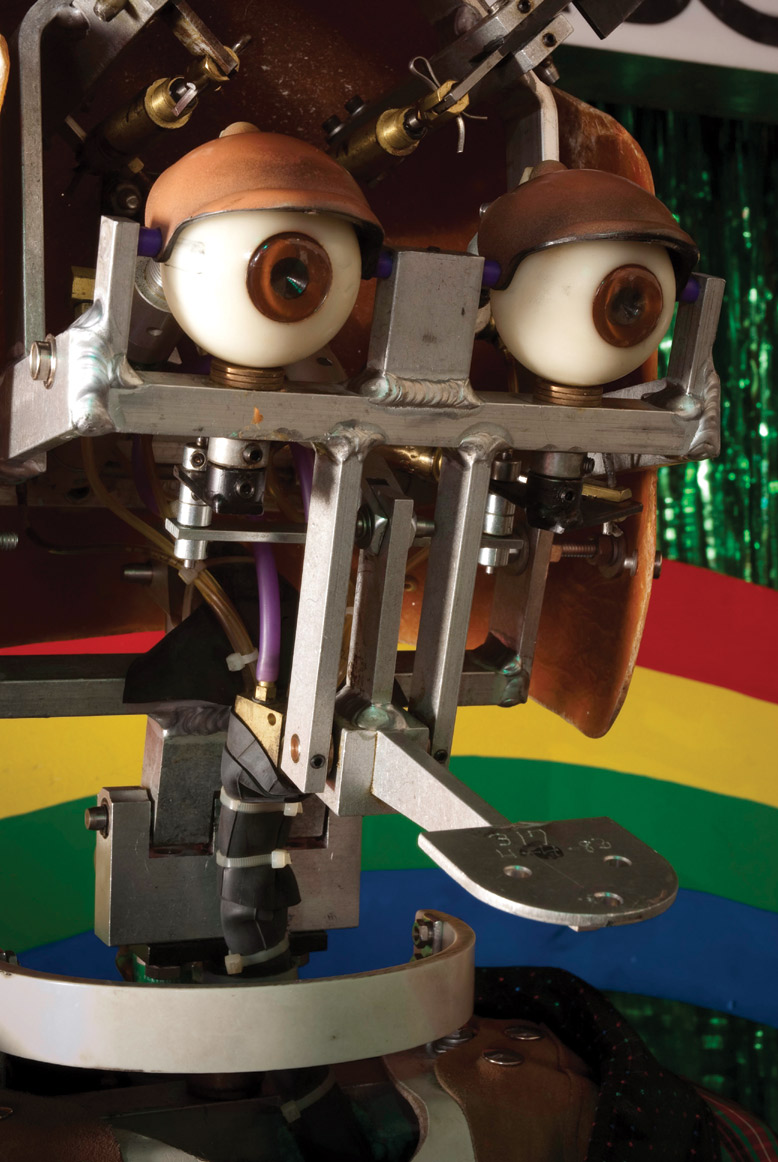

The Rock-afire robots are framed with an aluminum skeleton with fiberglass panels overlaid to create the shape of each character’s body. Leather flaps layed over joints gives a stiffer, more realistic look and prevents the costumes from pinching in the joints. Bronze bushings, steel pins, and pivots along with an array of air cylinders working in concert provide a fluid range of motion, and a durable design prevents a lot of major breakdowns.

“When they designed these robots, they did a good job of really making them robust,” Ferguson said.

The heads feature a lot of movement packed into a small frame, controlling eye, eyelid, mouth, and head turns (the latter of which turns down inside the body).

Enclosed cylinders in the robots heads control movements for the eyes, eyelids, and mouth. The heads turn inside the body.

The restaurants employed the services of a large 100 cubic feet per minute air compressor to fuel the robots — something that is not only impractical for residential use, but carries a price tag approaching or exceeding $10,000. The larger compressors run on 480 volts, while a standard residence is wired for 220 volts. Instead, he bought two smaller, more budget-friendly compressors: one that’s about 13 CFM and another that’s in the 7-8 CFM range.

That, he notes, is enough to run a 3-4 minute show, then pauses for an intermission of 2-3 minutes while the air tank refills. With dozens of moving parts to deal with, the machines of course require their share of upkeep. Ferguson chiefly runs his bots only on the weekends, saving the machines to a degree. He says he has to lubricate moving parts approximately bi-monthly, maybe a little more often during Indiana’s notoriously fickle summers, as moisture and humidity cause the valves and cylinders to stick.

Installation, Customization, and Tweaks

Ferguson was six years old the first time he went to Showbiz Pizza, and instantly fell in love. “It wasn’t so much the games,” he said. “It was the robots.”

Ferguson’s father was an engineer, and seeing the show in action at Showbiz grabbed Ferguson’s attention which still continues 25 years later. By the time he was 13, he was going several times a week, studying and observing the robots. “Something just bit me,” he said. “I was completely taken aback by how the robots moved. It just took over my life. I’m fascinated by every aspect of it.” Before he owned the robots, Ferguson said he found a sort of escape in listening to the old songs on vinyl. “Beyond the fact that the show is animatronically superior to any commercially available show near me, I have a love for the music and characters,” Ferguson said. “I could put on the old vinyl and as I listened to all the songs, it took me back to my childhood.”

Ferguson estimates he spent $5,000 to $6,000 on his set of robots, excluding accessories, travel expenses, maintenance, and electrical bills. Once he had them at his house, he had to find a way to creatively install them in his 20’ x 20’ two-car garage.

Aided by the original installation manuals — which he located with the help of some friends — he built a custom version of the three-stage layout to fit within his allotted space, placing the two secondary stages parallel to each other on either end of the main stage (in the restaurant layout the stages sat side-by-side).

Using the center curtain track of the main stage as a guide, Ferguson measured (“I had to trim a little of the curtains off,” he noted) then framed the center stage and floored the platform with plywood, cutting trap doors in the stage to access the air (MAC) valves which run under the stage to the compressors outside.

Ferguson installed insulation on his garage door, removed the garage door opener, and tightly braced the door closed. He painted the ceiling black and the walls red, and installed a backdrop.

After he installed the robots, he tracked down miscellaneous parts he was missing, and in some cases recreated them from scratch (most notably the hand puppet Earl’s body, and some of the background pieces on Billy Bob’s stage). Thus was born the room Ferguson and his friends know today as “Mitzi’s Mousetrap.”

Operating the Bots

The original animatronic computer used a reel-to-reel four-track audio system. The first two tracks comprised the audio for the show, and the remaining two transmitted data by way of a Manchester biphase datastream encoded with instructions that tell the pneumatic valves when to turn on and off. The control system converts the datastream to 240 separate channels that run to the characters. The original system ran on an analog signal. Ferguson, however, built a newer computer that he calls a “blue box” which allowed him to convert the signal to digital using a microcontroller, giving him greater flexibility in operating and maintaining the steel beasts. He no longer has to worry about calibrating the machines; their movements are more accurate; and he can bypass the outdated discreet semiconductors and troublesome adjustments of potentiometers.

The BlueBox

This also enabled him to use the more energy-efficient switching power supplies and throw out the old linear power supplies which ran on space-hogging transformers.

Not being content to merely relive his childhood, Ferguson sought to bring them into the 21st century, creating a C++-based software program that allows Ferguson to program the robots to customize the shows beyond their original set list of almost 200 songs, shows, and skits.

The software — dubbed “Programblue” — allows him to record the robots’ movements and data with to-the-millisecond timing on the audio. The movement data is tracked to the position of the audio, ensuring that the movements won’t fall out of sync if the audio slows down or speeds up.

The Bluebox interfaces to a standard computer using a single USB cable. This animatronic control system houses an outstanding 240 Darlington drivers, a hefty 24V switching supply, and necessary logic to talk with the Programblue software Ferguson wrote. Ferguson’s “blue box” enhances the operations of his show, making the robots operate more accurately to the music.

Adding the tracks is not as simple as pressing a button. Each robot must be programmed individually: leg, arm, head, mouth, and eye motions all have to be programmed separately. Ferguson estimates a three-minute song takes a minimum of six hours of work to program, moving upwards to a full day depending on the complexity of the choreography.

“That’s where the artistic part of it comes in,” he said. “It’s interesting to see what some of the other people come up with when they do a show.”

Ferguson also created Programblue to create container files that hold the data, meaning he can trade and exchange new programs with his fellow Rock-afire fanatics who have gotten copies of the software, then programmed their own custom shows.

Ferguson continuously tinkers with Programblue, adding new flourishes and making the program more user-friendly. Thus far, he’s added copy-and-paste capabilities for the character movements; worked using universal protocols (so that Programblue works with both his blue box and the original control computer); studio-type functionalities like rewind, fast forward, play, and pause that assist in setting movements; and created a 48-channel “microbox” — a smaller unit that allows users with partial shows to run the programs.

Ferguson adjusts an air cylinder on Fatz. Keeping the robots in top operating condition requires regular maintenance.

The Future

Ferguson hopes to use his Rock-afire set as a springboard into a robotics career; the larger concept of animatronics and control systems used to create toys, or possibly enter the home Halloween décor industry. He hopes his experiences with his set will launch his company — DSF Robots — as a viable means of making a living, with a certain band fronted by a gorilla and a country bear as his muse.

For now, he markets components to those he knows (Ferguson estimates that eight to 10 people around the country own a full set of the robots, with four of those up and running, while several more own individual pieces), and hopes he can help lead a revitalization of the animatronic entertainment industry.

“The Rock-afire Explosion is a tool of inspiration,” he said. “I’m a dreamer, and when I sit and watch the show, I dream up new ideas. It takes me to a place where I feel likeI can do anything.” SV

Article Comments