I Build BattleBots

By Andrea Suarez View In Digital Edition

I’m an engineer and robot builder. You most likely didn’t hesitate to believe that statement, because you can’t see that I also happen to be a woman. My name is Andrea and I am captain of Team Witch Doctor on the TV show, BattleBots™, where we compete our 250 lb robot against the best in the world.

I’ve received quite a bit of attention as a female captain. Most of it has been overwhelmingly positive and encouraging. I’ve had the privilege to speak to all kinds of BattleBots fans from all walks of life. I always get the same question: “How did you decide to become an engineer?” As a woman, my answer is expected to hold some unique wisdom or untapped secret. I’ve never had a good response because I don’t have a singular moment when I suddenly decided to be an engineer. I’ve been working on answering this question for a long time.

Team Witch Doctor, as seen on BattleBots on Discovery channel.

Photo by Daniel Longmire.

No one has ever thrown their arms in the air and yelled that I don’t belong. I often reassure young girls who are anxious about entering the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) community that my daily experience as a woman in STEM has truly been wonderful.

The hardest part of being a woman in a STEM field is subtler than anyone imagines.

Whenever I introduce myself as an engineer, I often get a surprised look and a “Really?” that I have to answer with evidence of my merit as an engineer. The comment section of our BattleBots posts are often sprinkled with doubt about whether my gender is the reason we were selected for the show, favored in a judges’ decision, etc. Every puzzled look instills doubt in my own abilities and is another reminder that I’m doing something that isn’t expected of me.

Because of this reality, I’ve made a very conscious effort on BattleBots to “show” instead of “tell.” I avoid every interview question about being a female robot builder, and refocus on the robot and the tournament. There’s no better way to help change perceptions than by doing what I do best: Building robots. Besides, young girls watching the show don’t need to be told what is right in front of them: If I can build 250 lb combat robots, so can they.

BattleBots fans around the world were shocked to see a brightly colored team with a female captain make it to the quarterfinals in Season 1.

High school is a defining time for most kids, and the same was true for me. I struggled to choose a school and went to a slew of open houses trying to find the right fit. I found my answer at an unexpected place: Carrollton School of the Sacred Heart, a small all-girls catholic school. The open house was run mostly by the students, with groups of girls exhibiting their classes and clubs.

While walking down a hall, I heard all sorts of whirring, squealing, and thumping coming from the chemistry lab. The sounds became impressively louder as I opened the door to the classroom. I walked inside and found all the tables on their side, forming a sort of gladiator arena in the middle of the room. A student welcomed me while gripping a daunting remote controller that took both hands to operate. I quickly realized that she was controlling a hefty metal machine with shiny black tires and sharp steel teeth that was painted like an alligator.

The girls introduced me to Gator — their 120 lb combat robot — and answered all the questions I fired at them. By the time I walked out of that room, the open house was over and I hadn’t seen the majority of the school, but I knew that this was where I belonged.

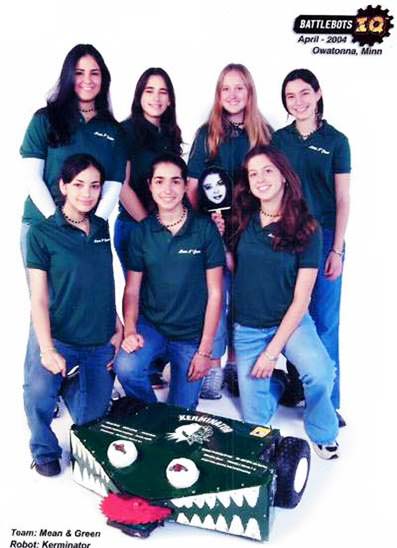

My first fighting robot, 120 lb Kerminator, as a high school sophomore in 2004. We had to learn how to weld, machine, cut, grind, and much more to build this machine! It didn’t win any awards, but it proved to us that we were robot builders.

Photo by Daniel Longmire.

By the time it became obvious that an all-girl robotics team was unusual, I was too committed to doubt whether I belonged in this sport. It was empowering to see that I could imagine a design and then make it happen. The more I learned — CAD design, machining, welding — the more power I had to make better robots, so I decided to study biomedical engineering. After all, the human body is just another machine; an incredibly complex robot. I like to joke that I got my start breaking things (robots), and then went on to fix things (bones).

As a sophomore in college, I applied for my first engineering internship with no relevant work experience on my resume. Instead of leaving that section blank, I wrote about “combat robotics.” I was shocked that every single question during my interview was related to robotics. The hiring manager asked me what voltage I was running, what battery chemistry I selected, and what motor specifications I chose. I was thrilled because I probably couldn’t answer any questions relevant to the position for which I was applying, but I could talk about robots all day.

I still work for him many years later, so I’ve had a chance to ask him about that interview. It turns out that he had never met a young lady that built robots. Once I was able to answer his questions, he hired me before I even left the interview room. I’ve spent the next 11 years designing and developing orthopedic trauma systems and I’m still — more often than not — the only woman in the room.

Just a couple of years ago, I was invited to speak at the Girl Powered panel at VEX Worlds, which is the largest robotics competition in the world. In that room, I saw hundreds of young girls who not only build robots, but are succeeding at the highest levels of competition. For the first time since I had stepped out of my all-girl high school, I felt I had nothing to prove.

Those girls didn’t once question if I was worthy of calling myself an engineer because they were already building robots themselves. If they could do it, then so could I. It was at that moment that I finally found my answer to the question that had stumped me so many times: “How did you decide to become an engineer?”

Team Mean n’ Green won second place at BattleBots IQ, with our full-body spinner Marvinator, as high school seniors in 2006. This remains a record for an all-female BattleBots team!

I decided to become an engineer because I believed it was possible. I had people in my life that took the time to introduce me to engineering and encouraged me as I developed the most basic skills at my own pace. I learned to use power tools as a teenager, and I was never compared to boys that had been using them in their dad’s garage since they were old enough to walk.

My mom never told me to stop welding when I got home from the shop with dirty hands and tiny burn holes in my high school uniform. Most importantly, any failures along the way were an expected part of any learning process; they were never attributed to my gender.

Girl Powered at VEX Worlds encourages hundreds of girls who are already succeeding at the highest level of robotics competitions.

Contrary to long-held stereotypes, boys aren’t naturally better builders than girls. The difference starts as toddlers, when they’re handed construction toys while we’re handed dolls. As a kid, I would beg my mom to say I was a boy at the McDonald’s drive-thru so that I would get a Transformer robot in my Happy Meal instead of a My Little Pony plush toy (as I hid in the back seat so the drive-thru attendant wouldn’t catch my lie). It’s no surprise that boys often have a head start on STEM skills, but it’s been my experience that — given a little encouragement — girls have no trouble quickly closing this gap.

Like most kids, I was told I could be anything I wanted to be: a doctor, an artist, an architect, even the president! I was already looking at colleges the first time I was told I could be an engineer. I’m an engineer in everything I do: my career, my hobbies, my lens of the world. I was an engineer before I knew what engineering meant. As a little kid, I was always finding ways to make things with my hands. And yet, I almost missed my calling because I didn’t know what to call it. You can’t dream to be something you don’t know exists.

Our robotics team at the University of Miami looked a little different than my high school team. This was the first time I really faced the gender gap in STEM and the team always treated me as an equal, which helped me build confidence as an engineer.

At Season 3 of BattleBots in 2018, only three of the 55 teams in the tournament were led by women. While men had 52 shots at the championship, the world’s opinion of whether women can build BattleBots was based on the performance of these three teams.

BattleBots has given me a platform to share my passion for robotics, and I hope it inspires young viewers to become builders.

The gender gap in STEM fields can be a daunting hurdle — especially as a beginner. While I used to be discouraged that strangers constantly needed convincing to believe my merit as an engineer, I now look forward to these opportunities.

I’m proud to be the first female robot builder to meet a skeptical BattleBots fan, if answering their questions means they’ll have higher regard for the next woman they meet in a STEM field. Each woman in STEM experiences the honor and burden of being a “first.” Everything is impossible up until a “first” proves it’s not.

I don’t have to be the first to fly across the Atlantic or launch into space to have the power to change our current culture. All I have to do — all any of us has to do — is encourage girls when they show interest in STEM activities, and fan that spark until the flame is strong enough to light its own path. It will be a brighter future for all of us.

Kids watching BattleBots often aspire to start learning how to build their own robots. My favorite part of this photo (besides their excitement) is that she’s wearing a princess shirt that reads “Follow your dreams.” Princesses can build robots too!

Soon, the next generation will be faced with the same question I struggled to answer for so long: “How did you decide to become an engineer?” I hope part of their answer will be that BattleBots showed them it was possible. SV

Article Comments